Armitt Library : A918.12

image:-

© see bottom of page

click to enlarge

Vol.1 opposite p.187 in Observations on Several Parts of England, Particularly the Mountains and Lakes of Cumberland Westmoreland, Relative Chiefly to Picturesque Beauty.

The list of plates in the preface of the book has:-

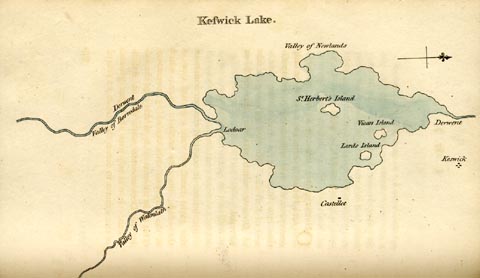

'XII. This plan of Keswick-lake means only to express the general shape of it; and the relative situation of it's several parts. Page 187.'

'The lake of Derwent, or Keswick-lake, as it is generally called, is contained within a circumference of about ten miles; presenting itself in a circular form, tho in fact it is rather oblong. It's area is interspersed with four or five islands; three of which only are of consequence, Lord's island, Vicar's island, and St. Herbert's island: but none of them is comparable to the island of Windermere, in point either of size, or beauty.

'If a painter were desirous of studying the circumference of the lake from one station, St. Herbert's island is the spot he should choose; from whence, as from a centre, he might see it in rotation. I have seena set of drawings taken from this stand; which were hung round a circular room, and intended to give a general idea of the boundaries of the lake. But as no representation could be given of the lake itself; the idea was lost, and the drawings made but an awkward appearance.

'Lord's island has it's name from being the place, where once stood a pleasure-house, belonging to the unfortunate family of Derwent-water, which took it's title from this lake. The ancient manor-house stood on Castle-hill above Keswick; where the antiquarian traces also the vestiges of a Roman fort. But an heiress of Derwent-water marrying into the family of the Ratcliffs; the family-seat was removed from Keswick to Dilston in Northumberland.

'As the boundaries of this lake are more mountainous than those of Windermere; they, of course afford more romantic scenery. But tho the whole shore, except the spot where we stood, is incircled with mountains; they rarely fall abruptly into the water; which is girt almost round by a margin of meadow - on the western shores especially. On the eastern, the mountains appraoch nearer the water; and in some parts fall perpendicularly into it. But as we stood viewing the lake from it's northern shores, all these marginal parts were lost; and the mountains (tho in fact they describe a circle of twenty miles, which is double the circumference of the lake) appeared universally to rise from the water's edge.

'Along it's western shores on the right, they rise smooth and uniform; and are therefore rather lumpish. The more removed part of this mountain-line is elegant: but, in some parts, it is disagreeably broken.

'On the eastern side, the mountains are both grnader, and more picturesque. The line is pleasing; and is filled with that variety of objects, broken-ground,- rocks,- and wood, which being well combined, take from the heaviness of a mountain; and give it an airy lightness.

'The front-skreen (if we may so call a portion of a circular form,) is more formidable, than either of the sides. But it's line is less elegant, than that of the eastern-skreen. The fall of Lodoar, which adorns that part of the lake, is an object of no consequence at the distance we now stood. But in our intended ride we proposed to take a nearer view of it.

'Of all the lakes in these romantic regions, the lake we are now examining, seems to be most generally admired. It was once admirable characterized by an ingenious person, [star] who, on his first seeing it, cried out, Jere is beauty indeed - Beauty lying in the lap of Horrour! We do not often find a happier illustration. Nothing conveys an idea of beauty more strobgly, than the lake; nor of horrour than the mountains; and the former lying in the lap of the latter, expresses in a strong manner the mode of their combination. The late Dr. Brown, who was a man of taste, and had seen every part of this country, singled out the scenery of this lake for it's peculiar beauty. [dagger] And unquestionably it is, in many places, both beautiful, and romantic; particluarly along it's eastern, and southern shores: but to give it pre-eminence may be paying it too high a compliment; as it would be too'

[footnote/star]

'The late Mr. Avilon, organist of St. Nicholas at Newcastle upon Tyne.'

[footnote/dagger]

'In a letter to Lord Lyttelton, quoted above.'

text continued:-

'rigourous to make any but a few comparative objections.

'In the first place, it's form, which in appearance is circular, is less interesting, I think, than the winding sweep of Windermere, and some other lakes; which losing themselves in cast reaches, behind some cape or promontory, add to their other beauties, the varieties of distance, and perspective. Some people object to this, as touching rather on the character of the river. but does that injure ir's beauty? And yet I believe there are very few rivers, which form such reaches, as those of Windermere.

'To the formality of it's shores may be added the formality of it's islands. They are round, regular, and similar spots, as they appear from most points of view; formal in their situation, as well as in their shape; and of little advantage to the scene. The islands of Windermere are in themselves better shaped; more varied; and uniting together, add beauty, contrast, and a peculiar feature to the whole.

'But among the greatest objections to this lake is the abrupt, and broken line in several of the mountains, which compose it's skreens, (especially on the western, and on part of the southern shore) which is more remarkable, than on any of the other lakes. We have little of the easy sweep of a mountain-line: at least the eye is hurt with too many tops of mountains, which injure the ideas of simplicity, and grandeur. Great care therefore should be taken in selecting views of this lake. If there is a littleness even among the grand ideas of the roiginal, what can we expect from representations on paper, or canvas? I have seen some views of this lake, injudiciously chosen, or taken on too extensive a scale, in which the mountains appear like hay-cocks.- I would be understood however to speak chiefly of the appearance, which the lines of these mountains occasionally make. When we change our point of view, the mountain-line changes also, and may be beautiful in one pount, tho it is displeasing in another.

'Having thus taken a view of the whole lake together from it's northern point, we proceeded on our rout to Borrodale, skirting the eastern coast along the edge of the water. The grandest side-skreen, on the left, hung over us; and we found it as beautifully romantic, and pleasing to the imagination, when it's rocks, precipices, and woods became a foreground; as it appeared from the northern point of the lake, when we examined it in a more removed point of view.

'Nor do these rocky shores recommend themselves to us only as foregrounds. We found them every where the happiest situations for obtaining the most picturesque views of the lake. The inexperienced conductor, shewing you the lake, carries you to some garish stand, where the eye may range far and and wide. Abd such a view indeed is well calculated, as we have just seen, to obtain a general idea of the whole. But he, who is in quest of the picturesque scenes of the lake, must travel along the rough side-skreens that adorn it; and catch it's beauties, as they arise in smaller portions - it's little bays, and winding shores - it's deep recesees, and hanging promontories - it's garnished rocks, and distant mountains. These are, in general, the picturesque scenes, which it affords.

'Part of this mountain is known by the name of Lady's-rake, from a tradition, that a young lady of Derwentwater family, in the time of some public disturbance, escaped a pursuit by climbing a precipice, which had been thought inaccessible.- A romantic place seldom wants a romantic story to adorn it.

'Detached from this continent of precipice, if I may so speak, stands a rocky hill, known by the name of Castellet. Under the beetling brow of this natural ruin we passed; and as we viewed it upwards from it's base, it seemed a fabric of such grandeur, that alone it was sufficient to give dignity to any scene. We were desried to take particular notice of it for a reason, which shall afterwards be mentioned.

'As we proceeded in our rout along the lake, the road grew wilder, and more romantic. There is not a more tremendous idea in travelling, than that of riding along the edge of a precipice, unguarded by any parapet, under impending rocks, which threaten above; while the surges of a flood, or the whirlpools of a rapid river, terrify below.

'...

'As we edged the precipices, we every where saw fragments of rock, and large stones scattered about, which being loosened by frosts and rains, had fallen from the cliffs above; and shew the traveller what dangers he has escaped.

'Once we found ourselves in hands more capricious than the elements. We rode along the edge of a precipice, under a steep woody rock; when some large stones came rolling from the top, and rushing through the thickets above us, bounded across the road, and plunged into the lake. At that instant we had made a pause to observe some part of the scenery; and by half a dozen yards escaped mischief. The wind was loud, and we conceived the stones had been dislodged by it's violence: but on riding a little farther, we discovered the real cause. High above our heads, at the summit of the cliff, sat a group of mountaineer children, amusing themselves with pushing stones from the top; and watching, as they plunged into the lake.- Of us they knew nothing, who were skreened from them by intervening thickets.

'As we approached the head of the lake, we were desired to turn round, and take a view of Castellet, tha rocky hill, which had appeared so enormous, as we stood under it. It had now shrunk into nothing in the midst of that scene of greatness, which surrounded it. I mention the circumstance, beacuse in these wild countries, comparison is the only scale used in the mensuration of mountains: at least it was the only scale, to which we were ever referred. In countries garced by a single mountain, the inhabitants may be very accurate in their investigation of it's height. The altitude and circumference of the Wreckin, I have no doubt, are accurately known in Shropshire: biut in a country like this, where chain is linked to chain, exactness would be endless.

'By this time we had approached the head of the lake; and could now distinguish the full sound of the fall of Lodoar; which had before reached our ears, as the wind suffered, indistinctly in broken notes.

'The water-fall is a noble object, both in itself, and as an ornament of the lake. It appears more as an object connected with the lake, as we approach by water. By land, we see it over a promontory of low ground, which, in some degree, hides it's grandeur. At the distance of a mile, it begins to appear with dignity.

'But of whatever advantage the fall of Lodoar may be as a piece of distant scenery, it's effect is very noble, when examined on the spot. As a single object, it wants no accompaniments of offskip; which would rather injure, than assist it. They would disturb it's simplicity, and repose. The greatness of it's parts affords scenery enough. Some instruments please in concert: others we wish to hear alone.

'The stream falls through a chasm between two towering perpendicular rocks. The intermediate part, broken into large fragments, forms the rough bed of the cascade. Some of these fragments stretching out in shelves, hold a depth of soil sufficient for large trees. Among these broken rocks the stream finds it's way through a fall of at least an hundred feet; and in heavy rains, the water is every way suited to the grandeur of the scene. Rocks and in opposition can hardly produce a more animated strife. The ground at the bottom is also very much broken, and over-grown with trees, and thiskets;amongst which the water is swallowed up into an abyss; and at length finds it's way, through deep channels, into the lake. We dismounted, and got as near as we could: but were not able to approach so near, as to look into the woody chasm, which receives the fall.

'Having viewed this grand piece of natural ruin, we proceeded in our rout towards the mountains of Borrodale; and shaping our course along the southern shores of the lake, we came to the river Derwent, which is a little to the west of Lodoar.

'These two rivers, the Lodoar, and the Derwent, furnish the chief supplies of Derwentwater. But those of the latter are much ampler. The Lodoar accordingly is lst in the lake: while the Derwent, first giving it's name to it, retains it's own to the sea.'

Keswick Lake.

Gilpin 1786 map

Gilpin 1786 map