16th-17th Centuries

Christopher Saxton

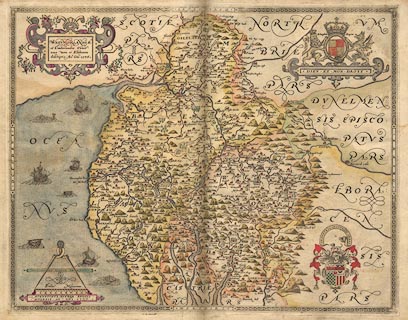

The first period of county maps begins with Christopher Saxton who surveyed the country in the 1570s, publishing a county atlas, the first ever such atlas:-

Saxton, Christopher: 1579: Atlas of England and Wales

His survey methods are uncertain. He had access to good instruments and the latest knowledge about surveying, but the time he had to carry out the government sponsored survey was limited. The best guess seems to be that he worked by simple methods perhaps, only perhaps, just using a compass and way wiser, added to local knowledge. Christopher Saxton's map of Westmorland and Cumberland is dated 1576. Its scale is about 5 map miles to 1 inch. Be wary of interpretting distances from his map; the mile used is not the modern statute mile but a customary measurement known now as the Old English Mile, of uncertain standing and uncertain length. Christopher Saxton's map mile is about 1 1/4 statute miles.

His maps were made to satisfy the needs of an elizabethan government which, following the lead of Henry VIII, was continuing a process of modernising the administration of England and Wales. William Cecil, Lord Burghley, Treasurer to Elizabeth I, used these maps and his was the motivation behind Christopher Saxton's survey.

Small versions of the map, separately for Westmorland and Cumberland, at 3.5 and 5 miles to 1 inch respectivley, were engraved and published in 1607 for:-

Camden, William: 1607 (6th edition, in Latin): Britannia

which includes extensive descriptive text about the counties. The complete text of the 1789 edition, with additions, is accessible in the Lakes Guides website.

Accuracy

A 16th century map maker, John Norden, comments on the problems of a map maker; for one, the problem of access to the land being surveyed, for another the problem of jokingly or maliciously wrong information being provided by local sources. He commented on accuracy, his own, or any map maker's:-

Because everye publique worke, is alwaies publiquely considered, and it is lawfull (I confesse) for all men, to utter their opinions therof freely as they finde it, and to call a fault a faulte. And because I cannot justifie all the Lineaments of so rude a body, I will saye with him that findes the fault (though in Art he cannot mend the same) Sir it is a fault and I will mend it if I can: But I have not yet seene the worke of the most absolute artist so perfect.

This nicely and accurately sums up my attitude to the a checklist of maps.

After Saxton

The maps that follow those of Christopher Saxton through the 17th century copy successively from one to another, and perhaps from some newer sources. There are some improvements, and there are errors of copying which are helped neither by unclear relationships between a symbol on the map and its label, nor by the language problems of dutch engravers who spoke no English working with english place names.

John Ogilby

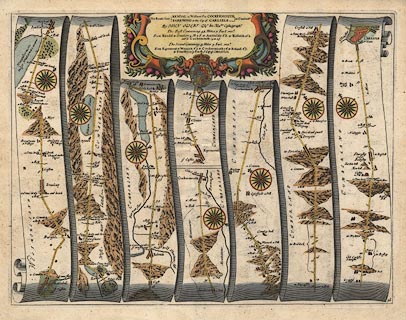

John Ogilby's survey of the roads of England and Wales in the 1670s is a different sort of mapping altogether. These maps are strip maps of the routes, the road is up the middle of a series of narrow 'scrolls' drawn on the sheet, and little of the surrounding countryside is plotted. 100 plates for 7519 miles of road were published in:-

Ogilby, John: 1675: Britannia

Four of the plates concern Westmorland, Cumberland etc. In the south of England the quality of this survey is excellent; matching John Ogilby's roads to modern days roads you will be amazed at the goodness of fit. But in the north, far from home and in rough terrain, the fit is not so good. The strip maps are to a scale about 1 mile to 1 inch, perhap setting the standard that is still popular. His mile is 1760 yards, what is now a statute mile. Though, again beware, quoted distances to places off the route tend to be in customary miles and some crowflight distances might be given. Ogilby's survey methods involved the use of a waywiser to measure distances. One of the aims of the survey was to delineate the post roads for letters, a central government responsibility.

John Ogliby commented on maps available in the 1670s, that they were mainly versions of Christopher Saxton's:-

more and more vitiated since by Transcribers and Copiers

and that the maps of the day were:-

Eminent for the Curious Performances of the Graver; their most Accurate Maps being but so many Guess-Plots.

And still in the mid 18th century the Gentlemens Magazine, vol.17 p.406, 1747, could say:-

... nothing is easier than to copy former maps, and old descriptions of counties, in most of which are numberless errors

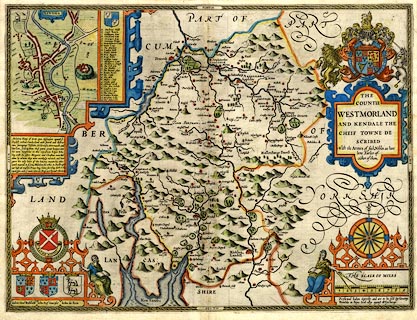

Map makers of the 17th and early 18th centuries copied from map to map, claims of new and accurate surveys notwithstanding. John Speed, William and John Blaeu, John Jansson, Richard Blome, John Seller, Robert Morden, Alexander Hogg, Herman Moll ... followed this way which was continued at least to John Harrison's map of 1788, which by that time really ought to have been better done. John Ogilby's strip maps were copied as well, by John Senex, Thomas Gardner, Emanuel Bowen, Thomas Kitchin, Carington Bowles ... all of them to a smaller scale, but more convenient for the traveller's pocket.

John Speed was honest about his copying; there is a famous quote from him in the introduction to his atlas:-

... I have put my sickle into other mens corne ...

Speed, John: 1611=1612: Theatre of the Empire of Great Britain: (London)

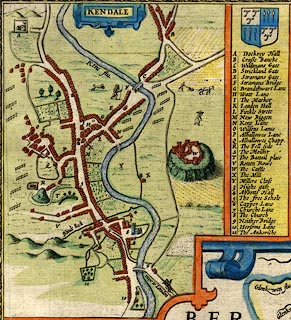

John Speed did add a new element, street maps.

Each county map has a town plan; the Westmorland map has Kendal, Cumberland has Carlisle. His atlas provides the first coherent set of town plans for the country, some of which, were made from his own surveys.

Sometimes a new map is not copied from the old but uses the original printing plate, perhaps 'improved' by deletions and new engraving. An engraved copper printing plate has a long life; its cost was not small; it is an asset not to be wasted. Plates were sold from publisher to publisher to be reprinted even a century or more later. There is a version of Christopher Saxton's map of 1576 published by Philip Lea in 1689 in which coats of arms are altered and added, a street map of Carlisle and roads across the counties are added, and other alterations made to the original copper plate, many decades after the original was drawn. Although the pace of change was much slower long ago such a gap assumes there was none! This map is probably the first road map of area, excluding the tiny playing card map by Robert Morden, 1676. It was still being published in 1772, nearly 200 years outofdate

Map History

Map History