goto source

goto sourcePage 1:- "BRIGANTES."

"BRITAIN, which hitherto has run out into several very large points towards Germany one way and towards Ireland the other, now withdraws itself as if it feared the violence of the ocean, and contracts the land into narrower compass. The coasts which now run on north strait to Scotland are not above 100 miles asunder. Almost all this part was in the flourishing times of Britain occupied by the BRIGANTES. Ptolemy says they inhabited the country from the eastern to the western sea. This was the most powerful and populous nation, most celebrated by the best writers, all of whom call them Brigantes, except Stephanus de Urbibus, who calls them Brigae, but the article in him relating to them ends abruptly in all the copies. If I should derive these Brigantes from Brigae, which among the antient Spaniards signified a city, I should not think it satisfactory, as Strabo says it is a Spanish word. If with Gropius I should suppose them so called from the Belgic language Brigantes, q.d. Free hands, I should be charged with putting off his reveries upon persons in their senses. Be it as it may, our Britans at present whenever they see a person acting in a profligate and imprudent manner make use of a common proverb Wharret Brigans, as much as to say he is playing the Brigant. The modern French from their antient language, as it should seem, call such sort of people Brigand, and piratic ships Brigantins. Whether this was the import of the word antiently in the Gaulish or British language I do not take upon me to affirm: but if I remember it right Strabo calls the Brigantes an Alpine nation marauders, and Julius, a young Belgian of daring intrepidity, who considered violence as authority, and virtue an empty name, is surnamed Briganticus in Tacitus. In this ill character our Brigantes seem to have been allied to these other nations, committing such outrages among their neighbours that Antoninus Pius on that account took away the greatest part of their country from them, as we learn from Pausanias who writes thus: "Antoninus Pius took away much territory from the Brigantes in Britain, because they invaded with an armed force and detained Genunia, a part of the country subject to the Romans." I hope none will consider this a reflection on these people, as it would be very inconsistent in me to brand any individual, much less an whole nation, with infamy. For this character in that warlike age, when all nations made right consist in force, was not accounted infamous. "Robbery," says Caesar, "is not held disgraceful in Germany, provided it is committed without the territories of each state. They say it serves to exercise their youth, and keep them employed." For a like reason the Paeones, a Greek nation, had their name as from

"As to Florianus del Campo, a Spanish author, affecting to bring our Brigantes from Spain to Ireland and thence into Britain with no other conjecture to support him but that he finds a city named Brigantia in his own country, I fear he misleads himself. For admitting our Brigantes and those in Ireland to have had their name from the same circumstance, I would rather with my very learned friend Thomas Savile suppose that some of the Brigantes and of other British nations after the arrival of the Romans retired to Ireland, some for peace and quiet, others to be out of sight of the Roman tyranny, and others not to lose their own concurrence in their old age that liberty which they received from nature at their birth. That Claudius was the first Roman who attacked our Brigantes and reduced them to his allegiance is intimated by Seneca in the following lines of his Apocolycinthosis:"

"--- ille Britannos

Ultra noti littora Ponti &caeruleos

Scuta Brigantes, dare Romuleis colla catenis

Jussit, &ipsum nova Romanae jura securis

Tremere Oceanum ---"

"By him subdued the Roman yoke,

The extremest Britans gladly took.

Him the blue shield Brigants ador'd

When the vast ocean felt his pow'r

Restrain'd with laws unknown before,

And trembling own'd a Roman Lord."

"I suppose them, however, not subdued by arms, but rather to have submitted upon conditions, as historians say nothing of what the poet here alludes to. Tacitus says that discords arising among the Brigantes at that"

goto source

goto sourcePage 2:- "time brought back Ostorius who was entring into a new war, and who soon put a stop to them by the execution of a few persons. At this time the Brigantes had a queen of their own Cartismandua, of great power and noble birth, who took and delivered Caratacus up to the Romans. Wealth and prosperity making her despise her husband Venutius, she made his armour-bearer Vellocatus partner of her bed and throne; the introduction of which infamy into the family occasioned a fatal war. The husband had on his side the affections of his subjects, the adulterer only the queen's passion and cruelty to support him. She by her artifices took off the brother and relations of Venutius, who provoked by this disgrace called in allies, and by their assistance and by the revolt of the Brigantes, which soon followed, reduced Cartismandua to extremities. On her applying to the Romans their light troops and cohorts after various engagements extricated her from her difficulties. The kingdom was however left to Venutius, and the management of the war to the Romans, who were not able to reduce the Brigantes before the time of Vespasian. Then Petilius Cerealis invaded their kingdom, fought many battles, sometimes bloody ones, and subdued or wasted the greatest part of the Brigantes. But whereas Tacitus says this queen of the Brigantes gave up Caratacus to Claudius, and that that emperor exhibited him in his triumph, it is certainly an antichronism in that excellent author, and some time since noticed as such by Lipsius that perfect master of the spirit of the antient writers. For neither was this Caratacus king of the Silures led in that triumph of Claudius, nor Caratacus son of Cunobeline (for so he is styled in Fasti, though by Dio Catacratus) over whom Aulus Plautius, if not the same year certainly the following, obtained an ovation. But this I leave to the discussion of others having treated of it before. In Hadrian's time when, as Spartian observes, "the Britans could not be kept in obedience to the Romans," our Brigantes also seem to have revolted from the Romans, and raised a rebellion. Had this not been the case there was no reason for Juvenal who wrote then to have thus expressed himself:"

"Dirue Maurorum attegias, castella Brigantum."

"The tents of Moors and Brigant castles sack."

"Nor do they seem to have been very quiet afterwards in the reign of Antoninus Pius who dispossessed them of part of their territory for making inroads into Genunia or Guinethia a province in alliance with the Romans, as we before observed."

"Might I be allowed by our critics who now take extraordinary liberties. I think I could correct two errors in Tacitus relative to the Brigantes. The first is in the 12th book of his Annals, where he says Venutius before-mentioned was of the state of the Jugantes; I would read of the Brigantes, which Tacitus himself seems to intimate in the 3d book of his History. The other is in his life of Agricola. The Brigantes under the command of a woman, began to fire the colony, &c, where historical truth obliges us to read the Trinobantes; for he is speaking of queen Boodicia who had nothing to do with the Brigantes, but had stirred up the Trinobantes to revolt, and driven out the colony at Camalodunum or Maldon."

"The very extensive country inhabited by these people which narrows as it runs, rises in the middle like the Appennines in Italy, with a continued ridge of mountains parting the counties, into which it is now divided. For under them to the east and German ocean lie the county of York and the bishopric of Durham; and to the west Lancashire, Westmoreland, and Cumberland; all which counties in the infancy of the Saxon government were comprehended in the kingdom of Deira. For the Saxons called these counties the kingdom of Northumberland, dividing it into two parts, calling that Deira or [Deir-land], which lies nearest to us on this side Tine, and Bernicia that which lies further on from the Tine to the Frith of Edenborough; both which parts had for some time kings of their own, but were at last united under one. I must just observe by the way, that whereas in the life of Charlemagne we read, that Eardulph, king of the Northumbrians, i.e. De Irland, being driven from his native country, took refuge with that prince, we must join the two words and read Deirland, and understand it of this kingdom and not of Ireland."

placename:- Brigantes

click to enlarge

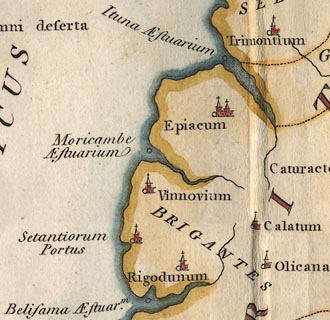

click to enlargePTY3Cm.jpg

"BRIGANTES"

item:- Hampshire Museums : FA2002.651

Image © see bottom of page

placename:- Brigantes

click to enlarge

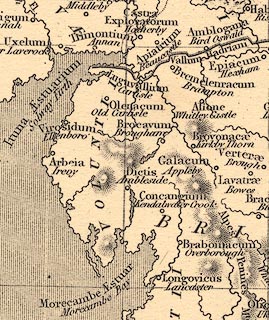

click to enlargeHOR1Cm.jpg

"BRIGANTES"

item:- JandMN : 429

Image © see bottom of page

placename:- Brigantes

click to enlarge

click to enlargePty1Cm.jpg

"Brigantes"

item:- private collection : 13

Image © see bottom of page