|

|

Gentleman's Magazine 1851 part 1 p.150

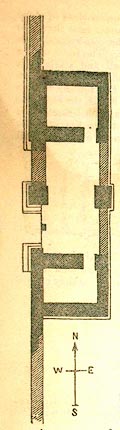

"All the gateways except the north have been explored, and

present very interesting subjects of study to the antiquary.

The western part is in the best condition, and is specially

worthy of attention. Its arrangements will readily be

understood by an inspection of the ground plan, which is

here introduced. ...

This gateway, as well as the others which have been, is, in

every sense of the word, double. Two walls must be passed

before the camp can be entered; each is provided with two

portals, and each portal has been closed with two-leaved

gates. The southern entrance of the outside wall has alone

as yet been entirely cleared of the masonry that closed it.

The jambs and pillars are formed of massive stones of rustic

masonry. The doors, if we may judge from the fragments of

corroded iron which have been lately picked up, were of

wood, strengthened with iron plates and studs; they moved,

as is appaprent from the pivot-holes, upon pivots of iron.

In the centre of each portal stands a strong upright stone,

against which the gates have shut. Some of the large

projecting stones of the exterior wall are worn, as if by

the sharpening of knives upon them. ... The guard-chambers

on each side are in a state of choice preservation, one of

the walls standing fourteen courses high. Were a roof put on

them, the antiquary might here stand guard, as the Tungrians

of old, and for a while forget that the world is sixteen

centuries older than it was when these chambers were reared.

At least two of the chambers in this part of the camp have

been warmed by U-shaped flues running round three of their

sides beneath the floor. These chambers, when recently

excavated, were found to be filled with rubbish so highly

charged with animal matter as painfully to affect the

sensibilities of the labourers. The teeth and bones of oxen,

horns resembling those of the red deer, but larger, and

boars' tusks were very abundant; there was the usual

quantity of all the kinds of pottery used by the Romans."

The Vignette subjoined to this article (in p.154) represents

the western portal of the station Amboglanna, now called

Birdoswald, as seen from the inside.

"It exhibits the pivot-holes of the gates, and the ruts worn

by the chariots or wagons of the Romans. The ruts are nearly

four feet two inches apart, the precise gauge of the

chariot-marks in the east gateway at Housesteads. The more

perfect of the pivot-holes exhibits a sort of spiral

grooving, which seems to have been formed with a view to

rendering the gate self-closing. The aperture in the sill of

the doorway, near the lower jamb, has been made designedly,

as a similar vacuity occurs in the eastern portal; perhaps

the object of it has been to allow of the passage of surface

water from the station. The whole of the area of the camp is

marked with the lines of streets and the ruins of

buildings."

In addition to these stations the wall was provided with

castella, now called Mile Castles, quadrangular in

form, and measuring usually from 60 to 70 feet in each

direction; and subsidiary to these were turrets or

watch-towers of about eight to ten feet square; the latter

of these have in comparatively recent times, been destroyed,

and the castella have not shared a much better fate.

In all these buildings it is remarkable that no tiles, so

common in the Roman structures in the south, have been used;

they are only to be found in the foundations and hypocausts

of the domestic edifices within the stations. By comparison,

many other points of difference will also be noticed. The

fortresses erected by the Romans on the line of the "Littus

Saxonicum" are of more imposing appearance, of wider area,

and possess higher architectural pretensions; but these two

great chains of stone fortresses, the maritime to repel the

Saxons and Franks, the inland to defend against the Picts

and Scots, were both admirably adapted for those purposes.

In the north, the wall itself was the main protection, and

the number of the castra was requisite to sustain

intercourse and rapid communication. In the south, the sea

was to a certain extent a defence,

|

next page

next page

Gents Mag 1851 part 1 p.150

Gents Mag 1851 part 1 p.150